Currently Available to Purchase

The furniture you see on this page is currently for sale. Please feel free to ask for additional pictures.

You can also visit our Face Book page at:

https://www.facebook.com/theshakercraftsmanyakima

Each piece is unique and is one of a kind in color and character and cannot be reproduced like modern made furniture. We can make something close, but each piece has its own character and charm.

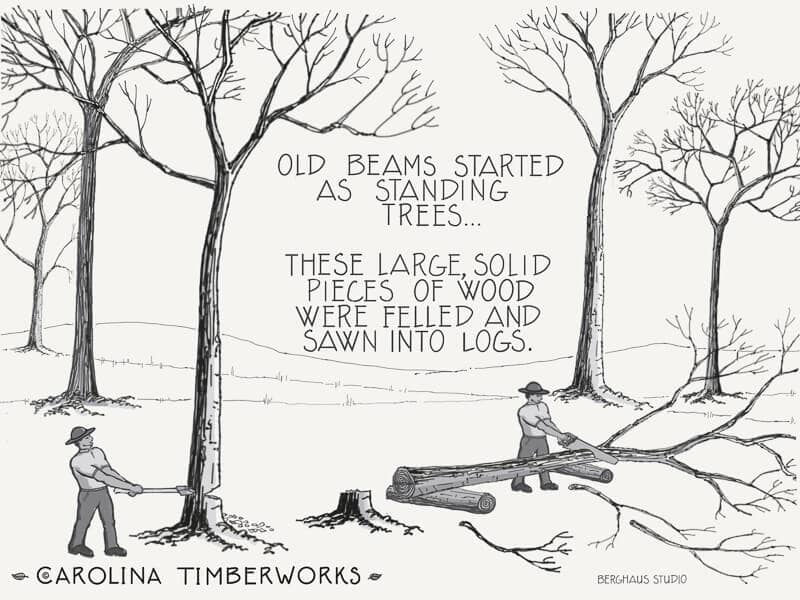

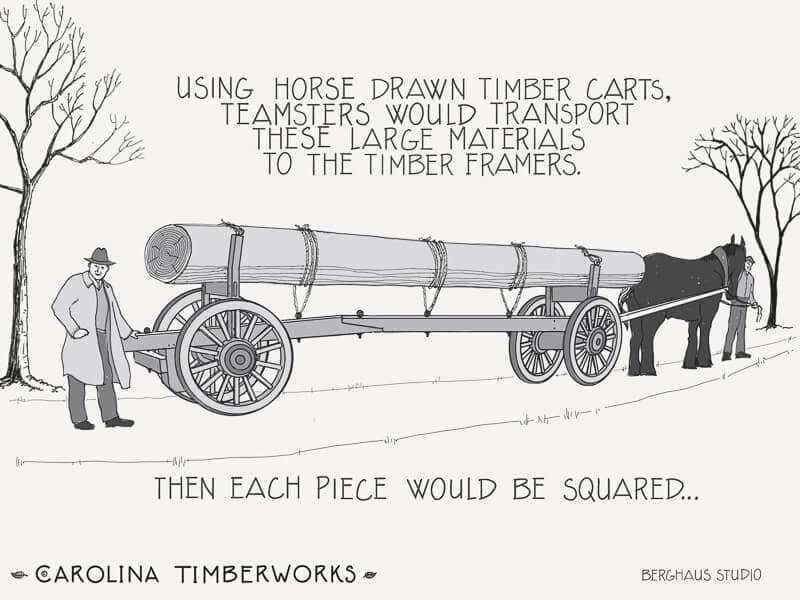

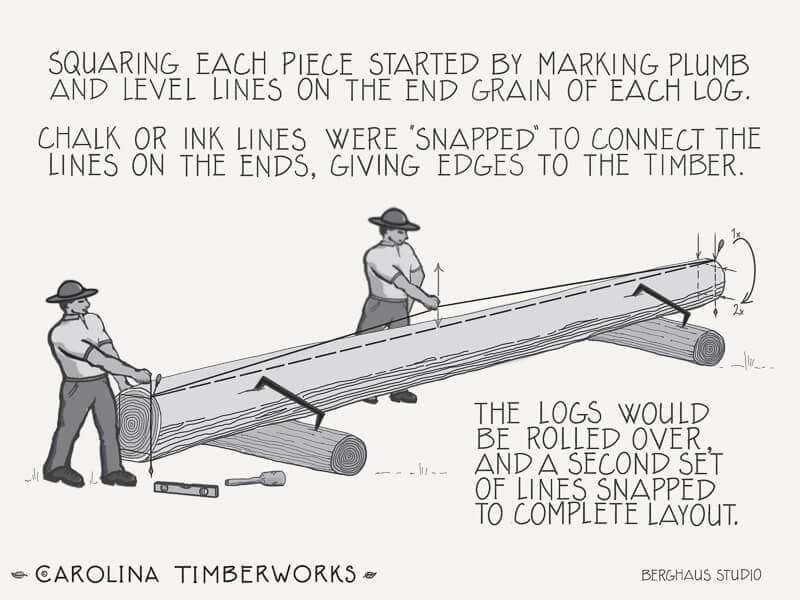

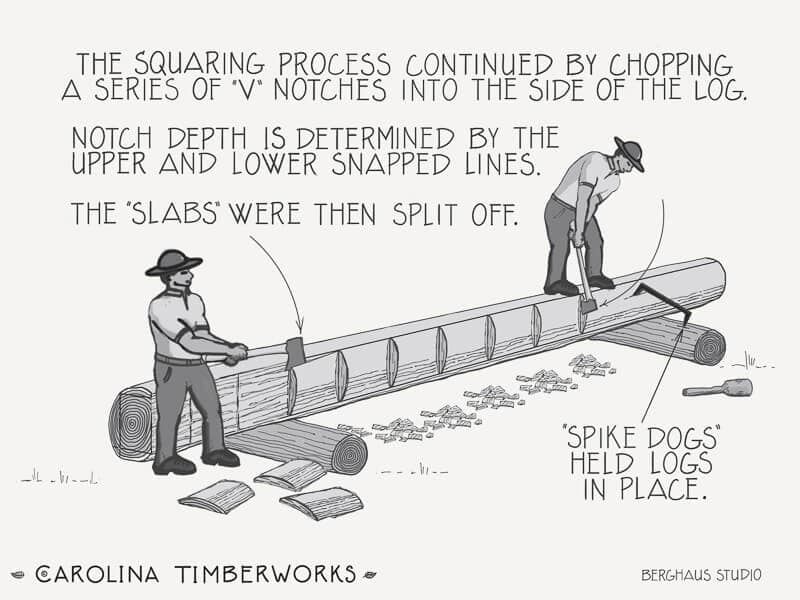

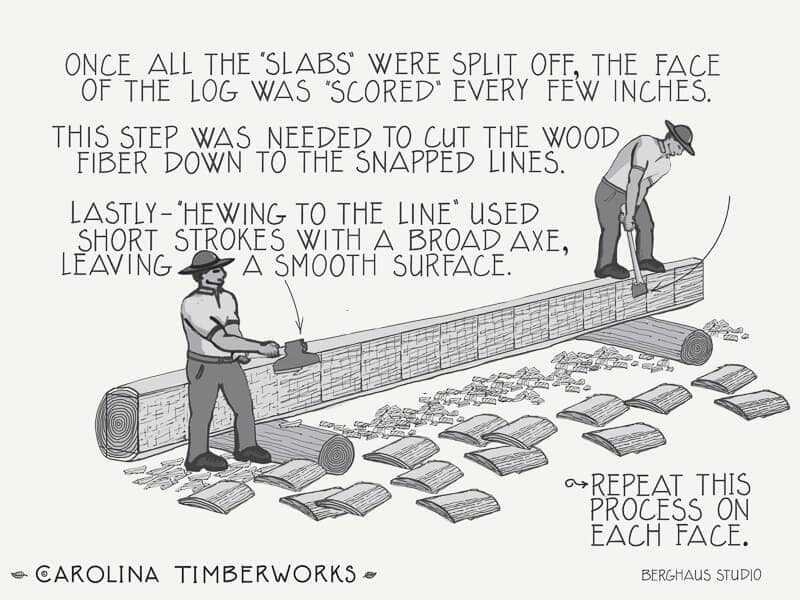

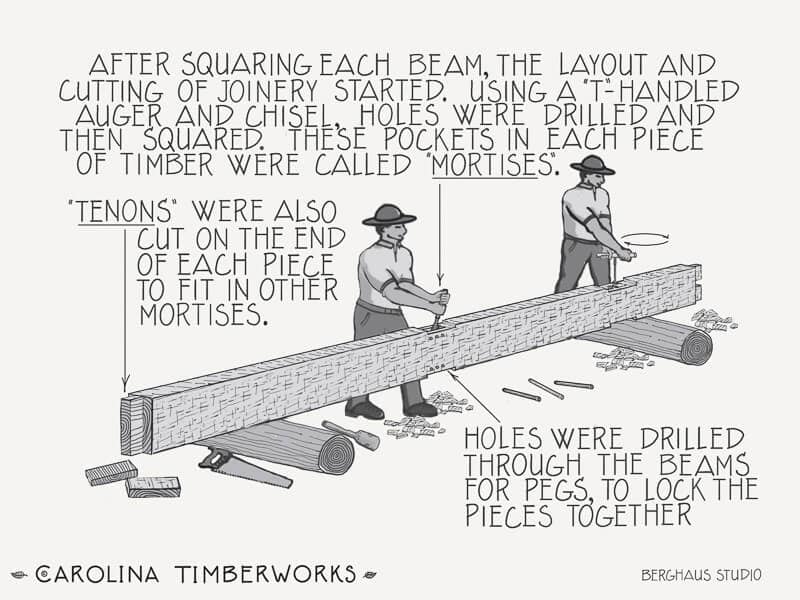

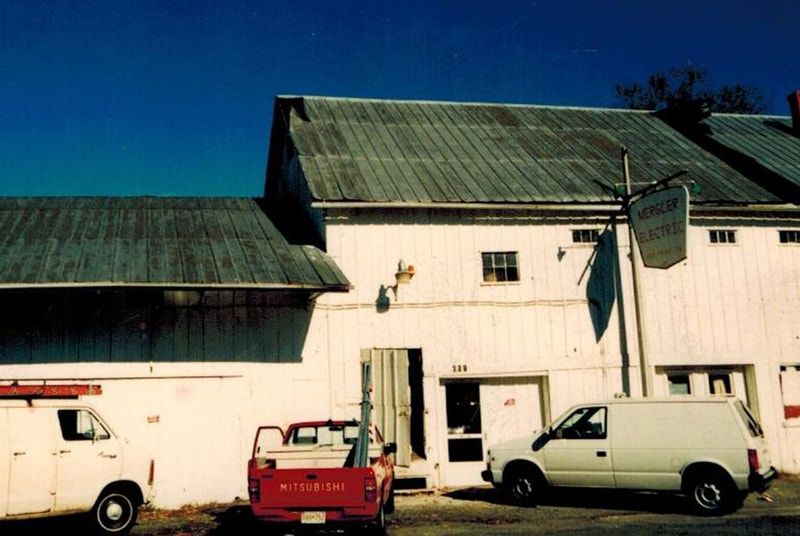

Hand Hewn Beams

The beams are real not the fake or new ones you see now days. They came from a barn built 175 years ago. The process is described below. Very hard and tedious work.

Black Cherry Sofa Table

Table was constructed using solid black cherry- no veneers or Para wood was used. The top has been spline-jointed and runs the entire length of each board. The top has been hand-scraped due to all the figure in the wood. The legs are mortised and pegged and do not come apart. Table has a waterproof and heat resistant finish so it will not leave rings. Table has been signed, numbered and dated. Table is currently going through a color change and will turn a beautiful brick red.

Black cherry (Prunus serotina), also known as wild black cherry, rum cherry and mountain black cherry, is found throughout most of the eastern United States. Most at home in the Allegheny Mountains of Pennsylvania and West Virginia, and in New York State, it can be found growing on a wide variety of sites: all those except for ones that display extreme wet or dry conditions. Common in the Catskills, black cherry can be seen growing at altitudes up to 3,200 feet and scattered throughout the valleys. Like other species, black cherry tells us something about the history of that forest. Being shade intolerant, it prefers to grow in open sunlight, and its presence tells us of a past disturbance that opened up or cleared the forest of the over-story allowing more sunlight to hit the forest floor. Because disturbances might include windstorm, logging or fire, this cherry is often found growing in areas that were once open pasture, or high up on ridges that are exposed to high winds.

Forest historians are not the only ones who value this species. Native Americans would boil the inner bark to make a concoction to treat colds, headaches, bronchitis, chest pains and the common cough. In fact, cherry extract is still used in commercial cough syrups. The pioneers would mix the cherries with brandy or rum in order to make cherry bounce, which provides a clue to the tree’s lesser-known common name, rum cherry.

It wasn’t until the turn of the century that black cherry wood became desirable by woodworkers and consumers alike. Once considered a poor substitute for mahogany, it is now the most valuable wood products species in North America. Because it draws such a high price, many landowners, foresters and wood products companies spend millions of dollars trying to perpetuate the species.

Sofa Table

60" l x 18" d x 30" T

$ 1095.00

Black cherry (Prunus serotina), also known as wild black cherry, rum cherry and mountain black cherry, is found throughout most of the eastern United States. Most at home in the Allegheny Mountains of Pennsylvania and West Virginia, and in New York State, it can be found growing on a wide variety of sites: all those except for ones that display extreme wet or dry conditions. Common in the Catskills, black cherry can be seen growing at altitudes up to 3,200 feet and scattered throughout the valleys. Like other species, black cherry tells us something about the history of that forest. Being shade intolerant, it prefers to grow in open sunlight, and its presence tells us of a past disturbance that opened up or cleared the forest of the over-story allowing more sunlight to hit the forest floor. Because disturbances might include windstorm, logging or fire, this cherry is often found growing in areas that were once open pasture, or high up on ridges that are exposed to high winds.

Forest historians are not the only ones who value this species. Native Americans would boil the inner bark to make a concoction to treat colds, headaches, bronchitis, chest pains and the common cough. In fact, cherry extract is still used in commercial cough syrups. The pioneers would mix the cherries with brandy or rum in order to make cherry bounce, which provides a clue to the tree’s lesser-known common name, rum cherry.

It wasn’t until the turn of the century that black cherry wood became desirable by woodworkers and consumers alike. Once considered a poor substitute for mahogany, it is now the most valuable wood products species in North America. Because it draws such a high price, many landowners, foresters and wood products companies spend millions of dollars trying to perpetuate the species.

Sofa Table

60" l x 18" d x 30" T

$ 1095.00

Sugar Pine Farm Table

Wood is Sugar Pine and came from an old hay barn. Table is constructed using no screws or nails. The table is constructed using mortise and tenon joints. The table has been hand planed. Top has been spline jointed. Table has a waterproof and heat resistant finish. Each piece is signed, numbered and dated. The barn was constructed in the 1860's in the town of La Grande, OR. Table is yellow tone. Florescent lights changing the color.

Farm Table

9.5 x 42"

$ 2795.00

Farm Table

9.5 x 42"

$ 2795.00

Doug Fir Farm Table

Wood is Douglas Fir and came from an old Saloon. End table is constructed using no screws or nails. All four corners of the drawer are done with hand-cut dovetails. The drawer slides on a sliding dovetail. The table is constructed using mortise and tenon joints. Drawer bottom is solid Doug fir and not plywood. The table has been hand planed. Table has a waterproof and heat resistant finish. Each piece is signed, numbered and dated.

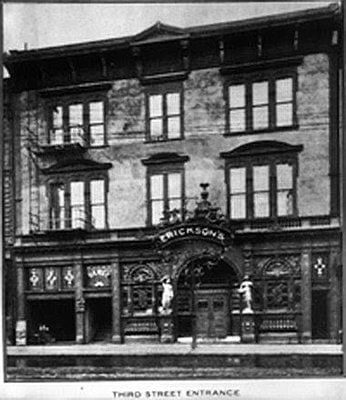

Erickson’s Saloon, sometimes called the Working Man’s Club or The Erickson Saloon, was a Portland establishment whose grandeur and notable size—epitomized by the 684-foot self-proclaimed “longest bar in the world” on its central drinking floor—ensured a national reputation that gave its glory years during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries an almost mythological reputation. The saloon’s lasting fame is largely attributable to writer Stewart Holbrook, whose 1954 Esquire article, “Elbow Bending for Giants,” remains the primary source for most writing on the subject. Stories about the saloon have become part of Portland lore and attest to the significance of Erickson’s among the laboring class.

August Erickson immigrated from Finland in the early 1880s. Within a decade, he had established himself as a charitable publican, admired among loggers and laborers and known in those early years for his honesty in business and his commitment to hospitality. Erickson built the first of several eponymous saloons on the block of Second Street and West Burnside in the part of Portland known as the North End.

The 1894 flood was a defining event in establishing the reputation of Erickson’s Saloon. Erickson stocked a barge with liquor and “dancers” outside his submerged bar, and the story is that patrons floated in on everything from a sloop to a log, with some staying until their money ran out.

The saloon Erickson rebuilt after the flood was the setting for the so-called legendary years immortalized by Holbrook, a period roughly dating from the flood of 1894 to a 1913 fire. The structure, rebuilt on a half-block-sized piece of land, had three stories of excess. The cavernous main hall on the first floor was home to the “longest bar” and, according to writer Wayne Curtis, featured a “$5,000 pipe organ,” a free museum, a music stage, and imported oil paintings. The second floor catered to the wealthy elite and featured private card parlors, sedate bars, and a sumptuous Gentlemen’s Grill with tuxedo-clad waiters. The third floor was given over to roofless cubicles known as “cribs” that hosted sex workers and mistresses.

The main hall echoed with the music of a band, the stomping of dancers, and the laughter of the clientele, providing what was for some an irresistible draw. One patron, writing anonymously in 1925 for the Loyal Legion of Loggers and Lumbermen’s Four L Bulletin in a memoir titled “Erickson’s: A Logger’s Reverie,” recalled how “loggers and ranchers, railroad men and miners, fisherman and sailors, prospectors, cowboys, Stakey men and stiffs; high and low, adventurers all, they came from everywhere” to revel in the “boisterous and hearty, but often rude spontaneity of rough men [who] had free rein.”

A free “Dainty Lunch” boasted a roast quarter steer, thick-cut bread, steamed clams, strong cheeses, mustards, and pickled fish—a substantial draw for working men. The selection of alcohol included sophisticated cocktails, an exclusive beer brewed by Henry Weinhard at an affordable nickel a pint, and cheap hard liquor that cost a quarter for two shots.

Erickson’s was an economic engine. The saloon employed at least thirty bartenders at the long bar alone, with additional bartenders at the other bars and a number of bouncers, bootblacks, sex workers, fruit sellers, waiters, dancers, musicians, card dealers, and chefs. The bartenders were notable for their meticulous mustaches and hair, as well as their wit, conversational skills, and general good nature. The bouncers were large and ferocious when confronted with those who insisted on breaking the saloon’s few iron-clad rules, among them a prohibition against begging and discussing politics or religion. Sex trafficking was a major part of the business. “At best,” Erickson’s 1925 obituary in the Oregonian noted, “the place August Erickson kept was a brothel, and at its worst it was an inspiration to rage and crime.”

The main clientele at Erickson’s was local, supplemented by tourists who brought in what former bouncer Spider Johnson estimated to be “50 to 500” customers at a time. It was also a center for itinerant laborers and a repository for messages delivered with the assumption that the recipient would eventually end up there. The writer in the Four L Bulletin remembered that the “songs of a dozen tongues” competed with one another in the main hall. The saloon was known as the House of All Nations for its willingness to serve foreigners, Blacks, and other minorities.

Erickson, an alcoholic, became the subject of frequent legal charges and arrests for offenses, including dispute over ownership of the saloon and illegal gambling. By 1906, he had sold a portion of his ownership to Fred Fritz Jr., who owned Fritz’s Saloon and Theater across the street, and J. J. Russell, who ran the Cabaret Grill next door, but he continued to work at the saloon as a manager and mascot, while also opening the Clackamas Tavern on Clackamas Road. After a 1913 fire damaged the saloon, he sold the remainder of his ownership to Fritz and Russell. He spent the rest of his life in penury and died in 1925.

The rebuilding of Erickson’s Saloon coincided with the advent of Oregon’s Prohibition laws in 1915. The bar sold soft drinks and “near beer” and charged for its once-free Dainty Lunch. By the time Prohibition was repealed, the saloon was a shadow of itself. The Fritz family owned the property until the 1960s, and the bar changed ownership multiple times over the years. An establishment with the name of “Erickson’s” operated on Second and Burnside before finally closing as Erickson’s Tavern in 1981.

Innovative Housing redeveloped the site as low-income apartments in the 2000s, using elements of the building’s history that included sections of the bar, a urinal trough, and a line of blue paint marking the height of the 1894 flood. A sign on the building identifies it as “Erickson’s Saloon 1895.”

Farm Table

6' x 36"

$1295.00

Thin Top

Bench

14' x 56"

$ 395.00

Chairs sold separately and are not included in price.

Erickson’s Saloon, sometimes called the Working Man’s Club or The Erickson Saloon, was a Portland establishment whose grandeur and notable size—epitomized by the 684-foot self-proclaimed “longest bar in the world” on its central drinking floor—ensured a national reputation that gave its glory years during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries an almost mythological reputation. The saloon’s lasting fame is largely attributable to writer Stewart Holbrook, whose 1954 Esquire article, “Elbow Bending for Giants,” remains the primary source for most writing on the subject. Stories about the saloon have become part of Portland lore and attest to the significance of Erickson’s among the laboring class.

August Erickson immigrated from Finland in the early 1880s. Within a decade, he had established himself as a charitable publican, admired among loggers and laborers and known in those early years for his honesty in business and his commitment to hospitality. Erickson built the first of several eponymous saloons on the block of Second Street and West Burnside in the part of Portland known as the North End.

The 1894 flood was a defining event in establishing the reputation of Erickson’s Saloon. Erickson stocked a barge with liquor and “dancers” outside his submerged bar, and the story is that patrons floated in on everything from a sloop to a log, with some staying until their money ran out.

The saloon Erickson rebuilt after the flood was the setting for the so-called legendary years immortalized by Holbrook, a period roughly dating from the flood of 1894 to a 1913 fire. The structure, rebuilt on a half-block-sized piece of land, had three stories of excess. The cavernous main hall on the first floor was home to the “longest bar” and, according to writer Wayne Curtis, featured a “$5,000 pipe organ,” a free museum, a music stage, and imported oil paintings. The second floor catered to the wealthy elite and featured private card parlors, sedate bars, and a sumptuous Gentlemen’s Grill with tuxedo-clad waiters. The third floor was given over to roofless cubicles known as “cribs” that hosted sex workers and mistresses.

The main hall echoed with the music of a band, the stomping of dancers, and the laughter of the clientele, providing what was for some an irresistible draw. One patron, writing anonymously in 1925 for the Loyal Legion of Loggers and Lumbermen’s Four L Bulletin in a memoir titled “Erickson’s: A Logger’s Reverie,” recalled how “loggers and ranchers, railroad men and miners, fisherman and sailors, prospectors, cowboys, Stakey men and stiffs; high and low, adventurers all, they came from everywhere” to revel in the “boisterous and hearty, but often rude spontaneity of rough men [who] had free rein.”

A free “Dainty Lunch” boasted a roast quarter steer, thick-cut bread, steamed clams, strong cheeses, mustards, and pickled fish—a substantial draw for working men. The selection of alcohol included sophisticated cocktails, an exclusive beer brewed by Henry Weinhard at an affordable nickel a pint, and cheap hard liquor that cost a quarter for two shots.

Erickson’s was an economic engine. The saloon employed at least thirty bartenders at the long bar alone, with additional bartenders at the other bars and a number of bouncers, bootblacks, sex workers, fruit sellers, waiters, dancers, musicians, card dealers, and chefs. The bartenders were notable for their meticulous mustaches and hair, as well as their wit, conversational skills, and general good nature. The bouncers were large and ferocious when confronted with those who insisted on breaking the saloon’s few iron-clad rules, among them a prohibition against begging and discussing politics or religion. Sex trafficking was a major part of the business. “At best,” Erickson’s 1925 obituary in the Oregonian noted, “the place August Erickson kept was a brothel, and at its worst it was an inspiration to rage and crime.”

The main clientele at Erickson’s was local, supplemented by tourists who brought in what former bouncer Spider Johnson estimated to be “50 to 500” customers at a time. It was also a center for itinerant laborers and a repository for messages delivered with the assumption that the recipient would eventually end up there. The writer in the Four L Bulletin remembered that the “songs of a dozen tongues” competed with one another in the main hall. The saloon was known as the House of All Nations for its willingness to serve foreigners, Blacks, and other minorities.

Erickson, an alcoholic, became the subject of frequent legal charges and arrests for offenses, including dispute over ownership of the saloon and illegal gambling. By 1906, he had sold a portion of his ownership to Fred Fritz Jr., who owned Fritz’s Saloon and Theater across the street, and J. J. Russell, who ran the Cabaret Grill next door, but he continued to work at the saloon as a manager and mascot, while also opening the Clackamas Tavern on Clackamas Road. After a 1913 fire damaged the saloon, he sold the remainder of his ownership to Fritz and Russell. He spent the rest of his life in penury and died in 1925.

The rebuilding of Erickson’s Saloon coincided with the advent of Oregon’s Prohibition laws in 1915. The bar sold soft drinks and “near beer” and charged for its once-free Dainty Lunch. By the time Prohibition was repealed, the saloon was a shadow of itself. The Fritz family owned the property until the 1960s, and the bar changed ownership multiple times over the years. An establishment with the name of “Erickson’s” operated on Second and Burnside before finally closing as Erickson’s Tavern in 1981.

Innovative Housing redeveloped the site as low-income apartments in the 2000s, using elements of the building’s history that included sections of the bar, a urinal trough, and a line of blue paint marking the height of the 1894 flood. A sign on the building identifies it as “Erickson’s Saloon 1895.”

Farm Table

6' x 36"

$1295.00

Thin Top

Bench

14' x 56"

$ 395.00

Chairs sold separately and are not included in price.

Doug Fir Farm Table

Table is constructed using Douglas Fir. Wood came from and old saloon. Table is constructed using no screws or nails other than what is holding the top down. Base is mortised and pegged and will not come apart. The top has been hand planed and spline jointed-this runs the entire length of each board. Table has a waterproof and heat resistant finish. Table has been signed, numbered and dated,

Erickson’s Saloon, sometimes called the Working Man’s Club or The Erickson Saloon, was a Portland establishment whose grandeur and notable size—epitomized by the 684-foot self-proclaimed “longest bar in the world” on its central drinking floor—ensured a national reputation that gave its glory years during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries an almost mythological reputation. The saloon’s lasting fame is largely attributable to writer Stewart Holbrook, whose 1954 Esquire article, “Elbow Bending for Giants,” remains the primary source for most writing on the subject. Stories about the saloon have become part of Portland lore and attest to the significance of Erickson’s among the laboring class.

August Erickson immigrated from Finland in the early 1880s. Within a decade, he had established himself as a charitable publican, admired among loggers and laborers and known in those early years for his honesty in business and his commitment to hospitality. Erickson built the first of several eponymous saloons on the block of Second Street and West Burnside in the part of Portland known as the North End.

The 1894 flood was a defining event in establishing the reputation of Erickson’s Saloon. Erickson stocked a barge with liquor and “dancers” outside his submerged bar, and the story is that patrons floated in on everything from a sloop to a log, with some staying until their money ran out.

The saloon Erickson rebuilt after the flood was the setting for the so-called legendary years immortalized by Holbrook, a period roughly dating from the flood of 1894 to a 1913 fire. The structure, rebuilt on a half-block-sized piece of land, had three stories of excess. The cavernous main hall on the first floor was home to the “longest bar” and, according to writer Wayne Curtis, featured a “$5,000 pipe organ,” a free museum, a music stage, and imported oil paintings. The second floor catered to the wealthy elite and featured private card parlors, sedate bars, and a sumptuous Gentlemen’s Grill with tuxedo-clad waiters. The third floor was given over to roofless cubicles known as “cribs” that hosted sex workers and mistresses.

The main hall echoed with the music of a band, the stomping of dancers, and the laughter of the clientele, providing what was for some an irresistible draw. One patron, writing anonymously in 1925 for the Loyal Legion of Loggers and Lumbermen’s Four L Bulletin in a memoir titled “Erickson’s: A Logger’s Reverie,” recalled how “loggers and ranchers, railroad men and miners, fisherman and sailors, prospectors, cowboys, Stakey men and stiffs; high and low, adventurers all, they came from everywhere” to revel in the “boisterous and hearty, but often rude spontaneity of rough men [who] had free rein.”

A free “Dainty Lunch” boasted a roast quarter steer, thick-cut bread, steamed clams, strong cheeses, mustards, and pickled fish—a substantial draw for working men. The selection of alcohol included sophisticated cocktails, an exclusive beer brewed by Henry Weinhard at an affordable nickel a pint, and cheap hard liquor that cost a quarter for two shots.

Erickson’s was an economic engine. The saloon employed at least thirty bartenders at the long bar alone, with additional bartenders at the other bars and a number of bouncers, bootblacks, sex workers, fruit sellers, waiters, dancers, musicians, card dealers, and chefs. The bartenders were notable for their meticulous mustaches and hair, as well as their wit, conversational skills, and general good nature. The bouncers were large and ferocious when confronted with those who insisted on breaking the saloon’s few iron-clad rules, among them a prohibition against begging and discussing politics or religion. Sex trafficking was a major part of the business. “At best,” Erickson’s 1925 obituary in the Oregonian noted, “the place August Erickson kept was a brothel, and at its worst it was an inspiration to rage and crime.”

The main clientele at Erickson’s was local, supplemented by tourists who brought in what former bouncer Spider Johnson estimated to be “50 to 500” customers at a time. It was also a center for itinerant laborers and a repository for messages delivered with the assumption that the recipient would eventually end up there. The writer in the Four L Bulletin remembered that the “songs of a dozen tongues” competed with one another in the main hall. The saloon was known as the House of All Nations for its willingness to serve foreigners, Blacks, and other minorities.

Erickson, an alcoholic, became the subject of frequent legal charges and arrests for offenses, including dispute over ownership of the saloon and illegal gambling. By 1906, he had sold a portion of his ownership to Fred Fritz Jr., who owned Fritz’s Saloon and Theater across the street, and J. J. Russell, who ran the Cabaret Grill next door, but he continued to work at the saloon as a manager and mascot, while also opening the Clackamas Tavern on Clackamas Road. After a 1913 fire damaged the saloon, he sold the remainder of his ownership to Fritz and Russell. He spent the rest of his life in penury and died in 1925.

The rebuilding of Erickson’s Saloon coincided with the advent of Oregon’s Prohibition laws in 1915. The bar sold soft drinks and “near beer” and charged for its once-free Dainty Lunch. By the time Prohibition was repealed, the saloon was a shadow of itself. The Fritz family owned the property until the 1960s, and the bar changed ownership multiple times over the years. An establishment with the name of “Erickson’s” operated on Second and Burnside before finally closing as Erickson’s Tavern in 1981.

Innovative Housing redeveloped the site as low-income apartments in the 2000s, using elements of the building’s history that included sections of the bar, a urinal trough, and a line of blue paint marking the height of the 1894 flood. A sign on the building identifies it as “Erickson’s Saloon 1895.”

Farm Table

7' x 42"

1595.00

Thin

Top

Bench Separate

$ 445.00 ea.

Erickson’s Saloon, sometimes called the Working Man’s Club or The Erickson Saloon, was a Portland establishment whose grandeur and notable size—epitomized by the 684-foot self-proclaimed “longest bar in the world” on its central drinking floor—ensured a national reputation that gave its glory years during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries an almost mythological reputation. The saloon’s lasting fame is largely attributable to writer Stewart Holbrook, whose 1954 Esquire article, “Elbow Bending for Giants,” remains the primary source for most writing on the subject. Stories about the saloon have become part of Portland lore and attest to the significance of Erickson’s among the laboring class.

August Erickson immigrated from Finland in the early 1880s. Within a decade, he had established himself as a charitable publican, admired among loggers and laborers and known in those early years for his honesty in business and his commitment to hospitality. Erickson built the first of several eponymous saloons on the block of Second Street and West Burnside in the part of Portland known as the North End.

The 1894 flood was a defining event in establishing the reputation of Erickson’s Saloon. Erickson stocked a barge with liquor and “dancers” outside his submerged bar, and the story is that patrons floated in on everything from a sloop to a log, with some staying until their money ran out.

The saloon Erickson rebuilt after the flood was the setting for the so-called legendary years immortalized by Holbrook, a period roughly dating from the flood of 1894 to a 1913 fire. The structure, rebuilt on a half-block-sized piece of land, had three stories of excess. The cavernous main hall on the first floor was home to the “longest bar” and, according to writer Wayne Curtis, featured a “$5,000 pipe organ,” a free museum, a music stage, and imported oil paintings. The second floor catered to the wealthy elite and featured private card parlors, sedate bars, and a sumptuous Gentlemen’s Grill with tuxedo-clad waiters. The third floor was given over to roofless cubicles known as “cribs” that hosted sex workers and mistresses.

The main hall echoed with the music of a band, the stomping of dancers, and the laughter of the clientele, providing what was for some an irresistible draw. One patron, writing anonymously in 1925 for the Loyal Legion of Loggers and Lumbermen’s Four L Bulletin in a memoir titled “Erickson’s: A Logger’s Reverie,” recalled how “loggers and ranchers, railroad men and miners, fisherman and sailors, prospectors, cowboys, Stakey men and stiffs; high and low, adventurers all, they came from everywhere” to revel in the “boisterous and hearty, but often rude spontaneity of rough men [who] had free rein.”

A free “Dainty Lunch” boasted a roast quarter steer, thick-cut bread, steamed clams, strong cheeses, mustards, and pickled fish—a substantial draw for working men. The selection of alcohol included sophisticated cocktails, an exclusive beer brewed by Henry Weinhard at an affordable nickel a pint, and cheap hard liquor that cost a quarter for two shots.

Erickson’s was an economic engine. The saloon employed at least thirty bartenders at the long bar alone, with additional bartenders at the other bars and a number of bouncers, bootblacks, sex workers, fruit sellers, waiters, dancers, musicians, card dealers, and chefs. The bartenders were notable for their meticulous mustaches and hair, as well as their wit, conversational skills, and general good nature. The bouncers were large and ferocious when confronted with those who insisted on breaking the saloon’s few iron-clad rules, among them a prohibition against begging and discussing politics or religion. Sex trafficking was a major part of the business. “At best,” Erickson’s 1925 obituary in the Oregonian noted, “the place August Erickson kept was a brothel, and at its worst it was an inspiration to rage and crime.”

The main clientele at Erickson’s was local, supplemented by tourists who brought in what former bouncer Spider Johnson estimated to be “50 to 500” customers at a time. It was also a center for itinerant laborers and a repository for messages delivered with the assumption that the recipient would eventually end up there. The writer in the Four L Bulletin remembered that the “songs of a dozen tongues” competed with one another in the main hall. The saloon was known as the House of All Nations for its willingness to serve foreigners, Blacks, and other minorities.

Erickson, an alcoholic, became the subject of frequent legal charges and arrests for offenses, including dispute over ownership of the saloon and illegal gambling. By 1906, he had sold a portion of his ownership to Fred Fritz Jr., who owned Fritz’s Saloon and Theater across the street, and J. J. Russell, who ran the Cabaret Grill next door, but he continued to work at the saloon as a manager and mascot, while also opening the Clackamas Tavern on Clackamas Road. After a 1913 fire damaged the saloon, he sold the remainder of his ownership to Fritz and Russell. He spent the rest of his life in penury and died in 1925.

The rebuilding of Erickson’s Saloon coincided with the advent of Oregon’s Prohibition laws in 1915. The bar sold soft drinks and “near beer” and charged for its once-free Dainty Lunch. By the time Prohibition was repealed, the saloon was a shadow of itself. The Fritz family owned the property until the 1960s, and the bar changed ownership multiple times over the years. An establishment with the name of “Erickson’s” operated on Second and Burnside before finally closing as Erickson’s Tavern in 1981.

Innovative Housing redeveloped the site as low-income apartments in the 2000s, using elements of the building’s history that included sections of the bar, a urinal trough, and a line of blue paint marking the height of the 1894 flood. A sign on the building identifies it as “Erickson’s Saloon 1895.”

Farm Table

7' x 42"

1595.00

Thin

Top

Bench Separate

$ 445.00 ea.

Black Cherry Farm table

Table was constructed using solid black cherry- no veneers or Para wood was used. The top has been spline-jointed and runs the entire length of each board. The top has been hand-scraped due to all the figure in the wood. The legs are mortised and pegged and do not come apart. Table has a waterproof and heat resistant finish so it will not leave rings. Table has been signed, numbered and dated. Table is currently going through a color change and will turn a beautiful brick red.

Black cherry (Prunus serotina), also known as wild black cherry, rum cherry and mountain black cherry, is found throughout most of the eastern United States. Most at home in the Allegheny Mountains of Pennsylvania and West Virginia, and in New York State, it can be found growing on a wide variety of sites: all those except for ones that display extreme wet or dry conditions. Common in the Catskills, black cherry can be seen growing at altitudes up to 3,200 feet and scattered throughout the valleys. Like other species, black cherry tells us something about the history of that forest. Being shade intolerant, it prefers to grow in open sunlight, and its presence tells us of a past disturbance that opened up or cleared the forest of the over-story allowing more sunlight to hit the forest floor. Because disturbances might include windstorm, logging or fire, this cherry is often found growing in areas that were once open pasture, or high up on ridges that are exposed to high winds.

Forest historians are not the only ones who value this species. Native Americans would boil the inner bark to make a concoction to treat colds, headaches, bronchitis, chest pains and the common cough. In fact, cherry extract is still used in commercial cough syrups. The pioneers would mix the cherries with brandy or rum in order to make cherry bounce, which provides a clue to the tree’s lesser-known common name, rum cherry.

It wasn’t until the turn of the century that black cherry wood became desirable by woodworkers and consumers alike. Once considered a poor substitute for mahogany, it is now the most valuable wood products species in North America. Because it draws such a high price, many landowners, foresters and wood products companies spend millions of dollars trying to perpetuate the species.

Farm Table

6' x 42"

$ 1895.00

Thick Top

Chairs sold separately.

American Chestnut Farm Table

Table is constructed using no screws or nails. The top has been spline-jointed that runs the entire length of each board. The top has been hand-planed. The legs are mortised and pegged and do not come apart. Table has a waterproof and heat resistant finish so it will not leave rings. Table has been signed, numbered and dated. The saw marks are from a steam saw and not today's fake saw marks. Wood is American Chestnut and is on the extinction list.

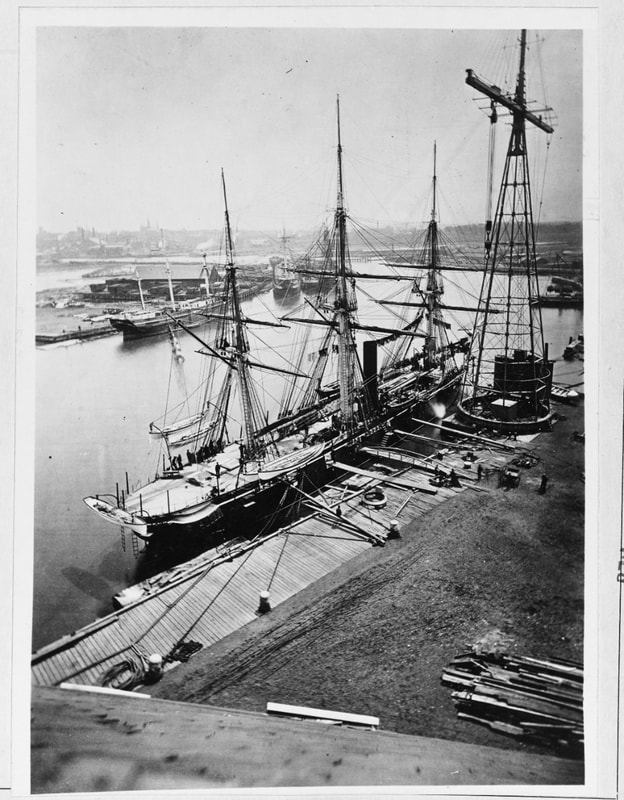

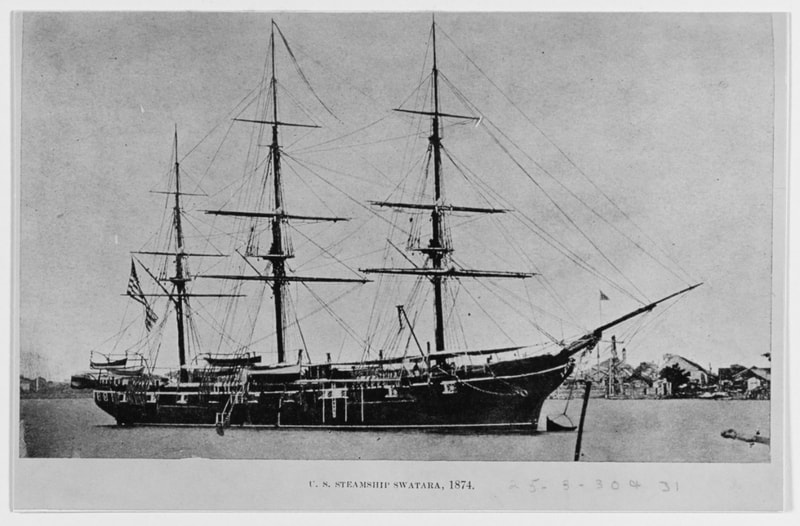

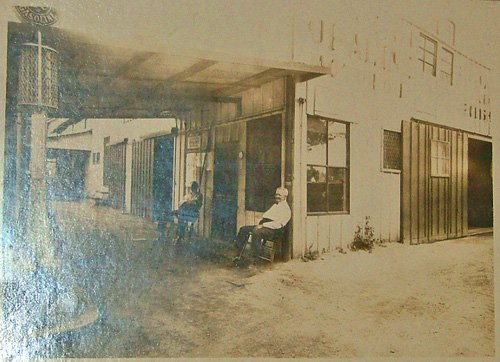

Wood came from an old Livery that was built in the 1840's. Building was located in Havre De Grace Maryland. Family has a huge historical significance in history and was involved in the underground railroad. Slaves would cross the river into town and would connect with the Currrier family. They would hide them until nightfall in their home (which had secret passages) and take them down to the ferry in which another of the family owned several large boats.

Another one of the brothers was famous for being the ship captain that brought back John Surratt from Egypt on the Monitor to be tried for the Lincoln Assassination.

Jane Currier of the Currier House B&B graciously shared a handful of the thousands of pieces of papers, receipts and photographs that were found in the house during renovations.

Jane’s Aunt “Honey” lives* in Susquehanna Hills and remembers life at the livery stable. She recalls being told that around 1892 the livery stable was located on Pearl Street. She thinks it was about that time it was moved to Franklin & Union for a short while. Then it was moved to Franklin & Stokes Street where the building once stood.

Jane’s grandfather, O.R. Currier, operated the Havre de Grace Livery Stable until his death in 1939. The livery stabled 36 horses on a permanent basis. Fifteen horses were kept on the second floor with the office and tack room. The balance was kept on the first floor along with the large wagon that was used with the three Clydesdale horses.

Aunt “Honey” remembers that there were two funeral hearses: a gray for younger people pulled by gray horses and a black one for older people pulled by black horses. They also had sleighs and buggies.

Honey also recalls that the hay was kept on the third floor. Now picture this: a pulley system was used to get the hay to the third floor. A horse was tied to the pulley system and had to walk more than half a block away to be able to pull the hay high enough to get it in through the third-floor window.

The livery stable papers can really tell a great deal about the city’s history. Moving loads of raw materials and finished goods to the canals, the wharf and the trains kept O.R. Currier well aware of what was happening in town. Receipts for lumber being delivered would tell when and whose house or building was being constructed.

The large wagon and Clydesdale horses would move heavy loads of building materials and pick up shipments from the Pennsylvania Railroad and also the wharf at the foot of Otsego Street. Tons of sand were being purchased here for delivery to the railroad and ships at the wharf. Another unique fact was that there are many receipts from Texaco, presumably kerosene oil for lamps, etc. since these were dated before automobiles.

Honey remembers that the Vandiver horses were kept at the livery. She also recalls that a large wagon was used to haul Havre de Grace people to Bel Air for jury duty, sporting events or any type of business. It was the only transportation before cars.

O.R. Currier rented out sleighs for races on Union Avenue and the water’s edge when the ice was frozen. Called the Union Avenue Sleigh Races, they were evidently well organized. He also rented buggies and horses to salesmen who came to town on the PA Railroad.

In 1918 the horses, wagons and trappings were all sold to Guilding Nitrate Company. The livery was changed to a gas station and storage company to be prepared for changing times. In the Currier B&B a picture hangs of the first gas pump at the station.

O.R. Currier was also the first chief of the Susquehanna Hose Company. Most likely the horses at the livery made him very important to the fire company. He held that position for fifteen years.

There’s a great deal more to learn from the small pieces of information that Jane Currier shared with me. Consider these receipts:

$1.00 for 9 KWH of electricity used the month of May 1915

$17.15 for City Taxes in 1900 (tax on $2900.00)

10 new horse shoes for a total of $10.00

14925 gals. water consumed from June 27 to Sept 25, 1915 @ 30 cents per thousand gallons = $4.47

A total of $23.20 for carriage repairs and painting from June 24 to Nov. 17, 1915

American Chestnut

There were once almost 4 million American Chestnut trees in the United States. They were among the largest, tallest and fastest growing trees in the eastern forest. The wood was long-lasting, straight grained and suitable for furniture, fencing and building. The nuts fed billions of birds and animals. It was almost a perfect tree-that is, until it was killed by a blight a century ago. That blight has been called the greatest ecological disaster to strike the world's forests in all of history. A tree that had survived all adversaries for 40 million years had disappeared in 10 years. What was once known as the queen of Eastern America, the American Chestnut is now nearly extinct.

The American chestnut was an economic staple of the original homesteaders in the Appalachian Mountains. The wood was light weight, weather resistant, very easy to chop and mill by hand. Colonists used the trees not only for their homes but for fencing, rails and the nuts that they produced. They were known to grow up to 26" in diameter and if your farm had many American Chestnut trees you were considered to be a very wealthy farmer.

It is believed that in 1904 a forester from the Bronx Zoo brought in Asian Chestnut trees to decorate the Zoo. It was in these trees that a blight called Endothia Parasitica was born. The fungus, which was unintentionally brought to America, spread fast. In less than 10 years the American Chestnut was all but extinct. The root bases below the disease are still alive but the saplings that they produce do not live long. Researchers have spent the last 100 years trying to revive the species but to no avail. Our American Chestnuts are now gone.

Farm Table

sold

6' x 40"

$2995.00

Wood is extinct

Thin top

Farm Table

Bench and Chairs

Table is constructed using Douglas Fir. Wood came from and old grain elevator. Table is constructed using no screws or nails other than what is holding the top down. Base is mortised and pegged and will not come apart. The top has been hand planed and spline jointed. Table has a waterproof and heat resistant finish. Table has been signed, numbered and dated,

Chairs have a patent and contain no screws or nails. Chairs are considered to be ergonomically correct. All joints have been mortised and pegged.

Bench is constructed using no screws or nails. Joints have been mortised and pegged and do not come apart. The bench measures 66" long and fits between the legs of the table. Each piece has been signed, numbered and dated.

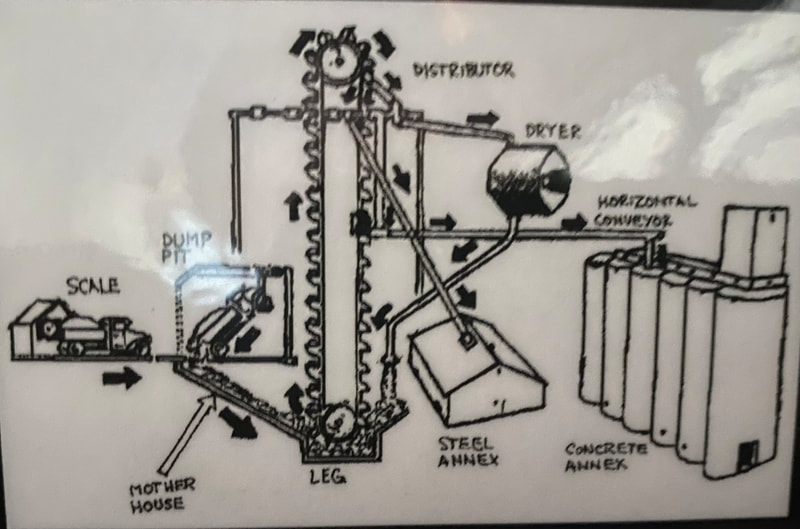

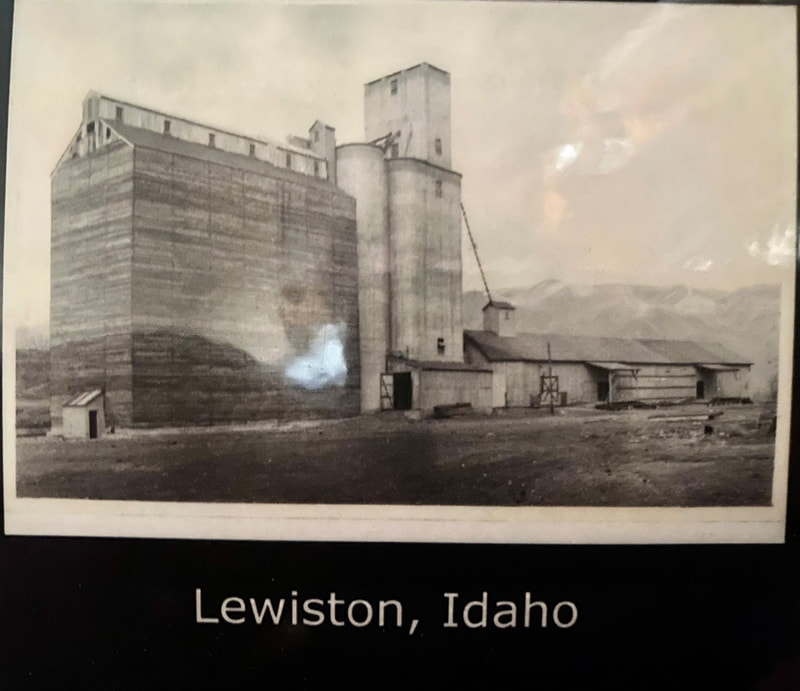

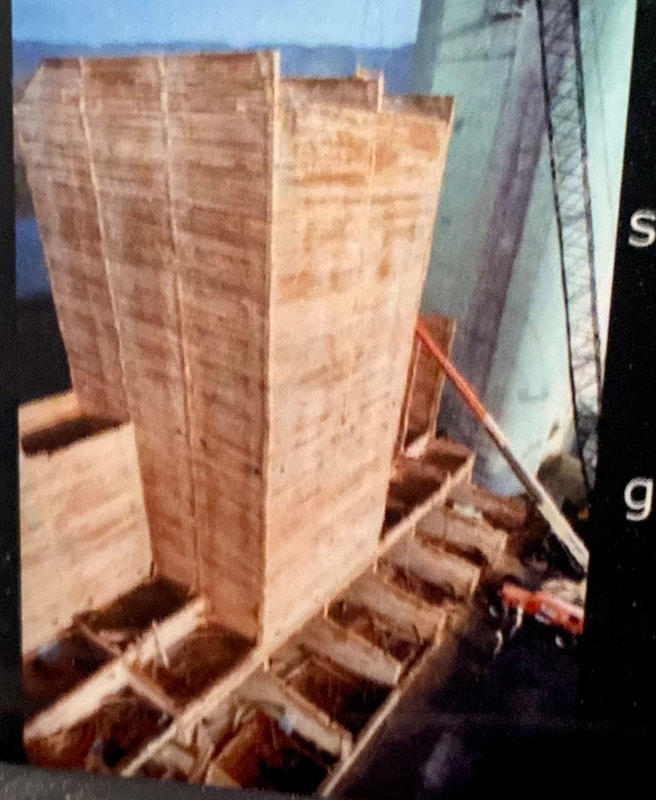

Wood came from an old grain elevator that belonged to Primeland Cooperative. Primeland Cooperative was originally formed as Lewiston Grain Growers, Inc. The elevator was created by the merging of several smaller elevator companies and it became the largest grain shipper on the railroad. This grain elevator was built in 1941 out of wood. Several of the grain elevators were moved to form this one so the exact date is unknown. This grain elevator held 165,000 bushels and was dismantled in 2013.

Farm Table

7' x 39"

Thin top

Can be sold separately

Four ladderback chairs and one bench

Chairs have a patent and contain no screws or nails. Chairs are considered to be ergonomically correct. All joints have been mortised and pegged.

Bench is constructed using no screws or nails. Joints have been mortised and pegged and do not come apart. The bench measures 66" long and fits between the legs of the table. Each piece has been signed, numbered and dated.

Wood came from an old grain elevator that belonged to Primeland Cooperative. Primeland Cooperative was originally formed as Lewiston Grain Growers, Inc. The elevator was created by the merging of several smaller elevator companies and it became the largest grain shipper on the railroad. This grain elevator was built in 1941 out of wood. Several of the grain elevators were moved to form this one so the exact date is unknown. This grain elevator held 165,000 bushels and was dismantled in 2013.

Farm Table

7' x 39"

Thin top

Can be sold separately

Four ladderback chairs and one bench

Dresser

CAMERA MAKING IT LOOK MORE RED THAN IT IS.

Wood is Douglas Fir and came from an old Saloon. Dresser is constructed using no screws or nails. All four corners of the drawers are hand cut dovetails. We use no metal in our dressers and use sliding dovetails and box joints on the drawers. The cabinet is constructed using mortise and tenon joints. The dresser is solid wood- we use no plywood or paper backing. The drawer bottoms and backing are also Doug Fir. The back is pegged on like the front not stapled. Each piece is signed, numbered and dated.

Erickson’s Saloon, sometimes called the Working Man’s Club or The Erickson Saloon, was a Portland establishment whose grandeur and notable size—epitomized by the 684-foot self-proclaimed “longest bar in the world” on its central drinking floor—ensured a national reputation that gave its glory years during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries an almost mythological reputation. The saloon’s lasting fame is largely attributable to writer Stewart Holbrook, whose 1954 Esquire article, “Elbow Bending for Giants,” remains the primary source for most writing on the subject. Stories about the saloon have become part of Portland lore and attest to the significance of Erickson’s among the laboring class.

August Erickson immigrated from Finland in the early 1880s. Within a decade, he had established himself as a charitable publican, admired among loggers and laborers and known in those early years for his honesty in business and his commitment to hospitality. Erickson built the first of several eponymous saloons on the block of Second Street and West Burnside in the part of Portland known as the North End.

The 1894 flood was a defining event in establishing the reputation of Erickson’s Saloon. Erickson stocked a barge with liquor and “dancers” outside his submerged bar, and the story is that patrons floated in on everything from a sloop to a log, with some staying until their money ran out.

The saloon Erickson rebuilt after the flood was the setting for the so-called legendary years immortalized by Holbrook, a period roughly dating from the flood of 1894 to a 1913 fire. The structure, rebuilt on a half-block-sized piece of land, had three stories of excess. The cavernous main hall on the first floor was home to the “longest bar” and, according to writer Wayne Curtis, featured a “$5,000 pipe organ,” a free museum, a music stage, and imported oil paintings. The second floor catered to the wealthy elite and featured private card parlors, sedate bars, and a sumptuous Gentlemen’s Grill with tuxedo-clad waiters. The third floor was given over to roofless cubicles known as “cribs” that hosted sex workers and mistresses.

The main hall echoed with the music of a band, the stomping of dancers, and the laughter of the clientele, providing what was for some an irresistible draw. One patron, writing anonymously in 1925 for the Loyal Legion of Loggers and Lumbermen’s Four L Bulletin in a memoir titled “Erickson’s: A Logger’s Reverie,” recalled how “loggers and ranchers, railroad men and miners, fisherman and sailors, prospectors, cowboys, stakey men and stiffs; high and low, adventurers all, they came from everywhere” to revel in the “boisterous and hearty, but often rude spontaneity of rough men [who] had free rein.”

A free “Dainty Lunch” boasted a roast quarter steer, thick-cut bread, steamed clams, strong cheeses, mustards, and pickled fish—a substantial draw for working men. The selection of alcohol included sophisticated cocktails, an exclusive beer brewed by Henry Weinhard at an affordable nickel a pint, and cheap hard liquor that cost a quarter for two shots.

Erickson’s was an economic engine. The saloon employed at least thirty bartenders at the long bar alone, with additional bartenders at the other bars and a number of bouncers, bootblacks, sex workers, fruit sellers, waiters, dancers, musicians, card dealers, and chefs. The bartenders were notable for their meticulous mustaches and hair, as well as their wit, conversational skills, and general good nature. The bouncers were large and ferocious when confronted with those who insisted on breaking the saloon’s few iron-clad rules, among them a prohibition against begging and discussing politics or religion. Sex trafficking was a major part of the business. “At best,” Erickson’s 1925 obituary in the Oregonian noted, “the place August Erickson kept was a brothel, and at its worst it was an inspiration to rage and crime.”

The main clientele at Erickson’s was local, supplemented by tourists who brought in what former bouncer Spider Johnson estimated to be “50 to 500” customers at a time. It was also a center for itinerant laborers and a repository for messages delivered with the assumption that the recipient would eventually end up there. The writer in the Four L Bulletin remembered that the “songs of a dozen tongues” competed with one another in the main hall. The saloon was known as the House of All Nations for its willingness to serve foreigners, Blacks, and other minorities.

Erickson, an alcoholic, became the subject of frequent legal charges and arrests for offenses, including dispute over ownership of the saloon and illegal gambling. By 1906, he had sold a portion of his ownership to Fred Fritz Jr., who owned Fritz’s Saloon and Theater across the street, and J. J. Russell, who ran the Cabaret Grill next door, but he continued to work at the saloon as a manager and mascot, while also opening the Clackamas Tavern on Clackamas Road. After a 1913 fire damaged the saloon, he sold the remainder of his ownership to Fritz and Russell. He spent the rest of his life in penury and died in 1925.

The rebuilding of Erickson’s Saloon coincided with the advent of Oregon’s Prohibition laws in 1915. The bar sold soft drinks and “near beer” and charged for its once-free Dainty Lunch. By the time Prohibition was repealed, the saloon was a shadow of itself. The Fritz family owned the property until the 1960s, and the bar changed ownership multiple times over the years. An establishment with the name of “Erickson’s” operated on Second and Burnside before finally closing as Erickson’s Tavern in 1981.

Innovative Housing redeveloped the site as low-income apartments in the 2000s, using elements of the building’s history that included sections of the bar, a urinal trough, and a line of blue paint marking the height of the 1894 flood. A sign on the building identifies it as “Erickson’s Saloon 1895.”

Dresser

60" w x 36" T x 18" D

$ 2995.00

No screws or nails in the construction

Hand cut dovetailed drawers (all four corners)

Solid wood construction no plywood or veneer

Erickson’s Saloon, sometimes called the Working Man’s Club or The Erickson Saloon, was a Portland establishment whose grandeur and notable size—epitomized by the 684-foot self-proclaimed “longest bar in the world” on its central drinking floor—ensured a national reputation that gave its glory years during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries an almost mythological reputation. The saloon’s lasting fame is largely attributable to writer Stewart Holbrook, whose 1954 Esquire article, “Elbow Bending for Giants,” remains the primary source for most writing on the subject. Stories about the saloon have become part of Portland lore and attest to the significance of Erickson’s among the laboring class.

August Erickson immigrated from Finland in the early 1880s. Within a decade, he had established himself as a charitable publican, admired among loggers and laborers and known in those early years for his honesty in business and his commitment to hospitality. Erickson built the first of several eponymous saloons on the block of Second Street and West Burnside in the part of Portland known as the North End.

The 1894 flood was a defining event in establishing the reputation of Erickson’s Saloon. Erickson stocked a barge with liquor and “dancers” outside his submerged bar, and the story is that patrons floated in on everything from a sloop to a log, with some staying until their money ran out.

The saloon Erickson rebuilt after the flood was the setting for the so-called legendary years immortalized by Holbrook, a period roughly dating from the flood of 1894 to a 1913 fire. The structure, rebuilt on a half-block-sized piece of land, had three stories of excess. The cavernous main hall on the first floor was home to the “longest bar” and, according to writer Wayne Curtis, featured a “$5,000 pipe organ,” a free museum, a music stage, and imported oil paintings. The second floor catered to the wealthy elite and featured private card parlors, sedate bars, and a sumptuous Gentlemen’s Grill with tuxedo-clad waiters. The third floor was given over to roofless cubicles known as “cribs” that hosted sex workers and mistresses.

The main hall echoed with the music of a band, the stomping of dancers, and the laughter of the clientele, providing what was for some an irresistible draw. One patron, writing anonymously in 1925 for the Loyal Legion of Loggers and Lumbermen’s Four L Bulletin in a memoir titled “Erickson’s: A Logger’s Reverie,” recalled how “loggers and ranchers, railroad men and miners, fisherman and sailors, prospectors, cowboys, stakey men and stiffs; high and low, adventurers all, they came from everywhere” to revel in the “boisterous and hearty, but often rude spontaneity of rough men [who] had free rein.”

A free “Dainty Lunch” boasted a roast quarter steer, thick-cut bread, steamed clams, strong cheeses, mustards, and pickled fish—a substantial draw for working men. The selection of alcohol included sophisticated cocktails, an exclusive beer brewed by Henry Weinhard at an affordable nickel a pint, and cheap hard liquor that cost a quarter for two shots.

Erickson’s was an economic engine. The saloon employed at least thirty bartenders at the long bar alone, with additional bartenders at the other bars and a number of bouncers, bootblacks, sex workers, fruit sellers, waiters, dancers, musicians, card dealers, and chefs. The bartenders were notable for their meticulous mustaches and hair, as well as their wit, conversational skills, and general good nature. The bouncers were large and ferocious when confronted with those who insisted on breaking the saloon’s few iron-clad rules, among them a prohibition against begging and discussing politics or religion. Sex trafficking was a major part of the business. “At best,” Erickson’s 1925 obituary in the Oregonian noted, “the place August Erickson kept was a brothel, and at its worst it was an inspiration to rage and crime.”

The main clientele at Erickson’s was local, supplemented by tourists who brought in what former bouncer Spider Johnson estimated to be “50 to 500” customers at a time. It was also a center for itinerant laborers and a repository for messages delivered with the assumption that the recipient would eventually end up there. The writer in the Four L Bulletin remembered that the “songs of a dozen tongues” competed with one another in the main hall. The saloon was known as the House of All Nations for its willingness to serve foreigners, Blacks, and other minorities.

Erickson, an alcoholic, became the subject of frequent legal charges and arrests for offenses, including dispute over ownership of the saloon and illegal gambling. By 1906, he had sold a portion of his ownership to Fred Fritz Jr., who owned Fritz’s Saloon and Theater across the street, and J. J. Russell, who ran the Cabaret Grill next door, but he continued to work at the saloon as a manager and mascot, while also opening the Clackamas Tavern on Clackamas Road. After a 1913 fire damaged the saloon, he sold the remainder of his ownership to Fritz and Russell. He spent the rest of his life in penury and died in 1925.

The rebuilding of Erickson’s Saloon coincided with the advent of Oregon’s Prohibition laws in 1915. The bar sold soft drinks and “near beer” and charged for its once-free Dainty Lunch. By the time Prohibition was repealed, the saloon was a shadow of itself. The Fritz family owned the property until the 1960s, and the bar changed ownership multiple times over the years. An establishment with the name of “Erickson’s” operated on Second and Burnside before finally closing as Erickson’s Tavern in 1981.

Innovative Housing redeveloped the site as low-income apartments in the 2000s, using elements of the building’s history that included sections of the bar, a urinal trough, and a line of blue paint marking the height of the 1894 flood. A sign on the building identifies it as “Erickson’s Saloon 1895.”

Dresser

60" w x 36" T x 18" D

$ 2995.00

No screws or nails in the construction

Hand cut dovetailed drawers (all four corners)

Solid wood construction no plywood or veneer

End Table

(Can go with the dresser)

Wood is Douglas Fir and came from an old Saloon. End table is constructed using no screws or nails. All four corners of the drawer are done with hand-cut dovetails. The drawer slides on a sliding dovetail. The table is constructed using mortise and tenon joints. Drawer bottom is solid Doug fir and not plywood. The table has been hand planed. Table has a waterproof and heat resistant finish. Each piece is signed, numbered and dated.

Erickson’s Saloon, sometimes called the Working Man’s Club or The Erickson Saloon, was a Portland establishment whose grandeur and notable size—epitomized by the 684-foot self-proclaimed “longest bar in the world” on its central drinking floor—ensured a national reputation that gave its glory years during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries an almost mythological reputation. The saloon’s lasting fame is largely attributable to writer Stewart Holbrook, whose 1954 Esquire article, “Elbow Bending for Giants,” remains the primary source for most writing on the subject. Stories about the saloon have become part of Portland lore and attest to the significance of Erickson’s among the laboring class.

August Erickson immigrated from Finland in the early 1880s. Within a decade, he had established himself as a charitable publican, admired among loggers and laborers and known in those early years for his honesty in business and his commitment to hospitality. Erickson built the first of several eponymous saloons on the block of Second Street and West Burnside in the part of Portland known as the North End.

The 1894 flood was a defining event in establishing the reputation of Erickson’s Saloon. Erickson stocked a barge with liquor and “dancers” outside his submerged bar, and the story is that patrons floated in on everything from a sloop to a log, with some staying until their money ran out.

The saloon Erickson rebuilt after the flood was the setting for the so-called legendary years immortalized by Holbrook, a period roughly dating from the flood of 1894 to a 1913 fire. The structure, rebuilt on a half-block-sized piece of land, had three stories of excess. The cavernous main hall on the first floor was home to the “longest bar” and, according to writer Wayne Curtis, featured a “$5,000 pipe organ,” a free museum, a music stage, and imported oil paintings. The second floor catered to the wealthy elite and featured private card parlors, sedate bars, and a sumptuous Gentlemen’s Grill with tuxedo-clad waiters. The third floor was given over to roofless cubicles known as “cribs” that hosted sex workers and mistresses.

The main hall echoed with the music of a band, the stomping of dancers, and the laughter of the clientele, providing what was for some an irresistible draw. One patron, writing anonymously in 1925 for the Loyal Legion of Loggers and Lumbermen’s Four L Bulletin in a memoir titled “Erickson’s: A Logger’s Reverie,” recalled how “loggers and ranchers, railroad men and miners, fisherman and sailors, prospectors, cowboys, stakey men and stiffs; high and low, adventurers all, they came from everywhere” to revel in the “boisterous and hearty, but often rude spontaneity of rough men [who] had free rein.”

A free “Dainty Lunch” boasted a roast quarter steer, thick-cut bread, steamed clams, strong cheeses, mustards, and pickled fish—a substantial draw for working men. The selection of alcohol included sophisticated cocktails, an exclusive beer brewed by Henry Weinhard at an affordable nickel a pint, and cheap hard liquor that cost a quarter for two shots.

Erickson’s was an economic engine. The saloon employed at least thirty bartenders at the long bar alone, with additional bartenders at the other bars and a number of bouncers, bootblacks, sex workers, fruit sellers, waiters, dancers, musicians, card dealers, and chefs. The bartenders were notable for their meticulous mustaches and hair, as well as their wit, conversational skills, and general good nature. The bouncers were large and ferocious when confronted with those who insisted on breaking the saloon’s few iron-clad rules, among them a prohibition against begging and discussing politics or religion. Sex trafficking was a major part of the business. “At best,” Erickson’s 1925 obituary in the Oregonian noted, “the place August Erickson kept was a brothel, and at its worst it was an inspiration to rage and crime.”

The main clientele at Erickson’s was local, supplemented by tourists who brought in what former bouncer Spider Johnson estimated to be “50 to 500” customers at a time. It was also a center for itinerant laborers and a repository for messages delivered with the assumption that the recipient would eventually end up there. The writer in the Four L Bulletin remembered that the “songs of a dozen tongues” competed with one another in the main hall. The saloon was known as the House of All Nations for its willingness to serve foreigners, Blacks, and other minorities.

Erickson, an alcoholic, became the subject of frequent legal charges and arrests for offenses, including dispute over ownership of the saloon and illegal gambling. By 1906, he had sold a portion of his ownership to Fred Fritz Jr., who owned Fritz’s Saloon and Theater across the street, and J. J. Russell, who ran the Cabaret Grill next door, but he continued to work at the saloon as a manager and mascot, while also opening the Clackamas Tavern on Clackamas Road. After a 1913 fire damaged the saloon, he sold the remainder of his ownership to Fritz and Russell. He spent the rest of his life in penury and died in 1925.

The rebuilding of Erickson’s Saloon coincided with the advent of Oregon’s Prohibition laws in 1915. The bar sold soft drinks and “near beer” and charged for its once-free Dainty Lunch. By the time Prohibition was repealed, the saloon was a shadow of itself. The Fritz family owned the property until the 1960s, and the bar changed ownership multiple times over the years. An establishment with the name of “Erickson’s” operated on Second and Burnside before finally closing as Erickson’s Tavern in 1981.

Innovative Housing redeveloped the site as low-income apartments in the 2000s, using elements of the building’s history that included sections of the bar, a urinal trough, and a line of blue paint marking the height of the 1894 flood. A sign on the building identifies it as “Erickson’s Saloon 1895.”

End table/bedside table

20" x 20" x 26" T

$ 895.00

Bedside or End table

(can go with dresser and end table pictured above)

Wood is Douglas Fir and came from an old Saloon. End table is constructed using no screws or nails. All four corners of the drawer are done with hand-cut dovetails. The drawer slides on a sliding dovetail. The cabinet is constructed using mortise and tenon joints. Drawer bottom is solid Doug fir and not plywood. The cabinet has been hand planed. Cabinet has a waterproof and heat resistant finish. Each piece is signed, numbered and dated.

Erickson’s Saloon, sometimes called the Working Man’s Club or The Erickson Saloon, was a Portland establishment whose grandeur and notable size—epitomized by the 684-foot self-proclaimed “longest bar in the world” on its central drinking floor—ensured a national reputation that gave its glory years during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries an almost mythological reputation. The saloon’s lasting fame is largely attributable to writer Stewart Holbrook, whose 1954 Esquire article, “Elbow Bending for Giants,” remains the primary source for most writing on the subject. Stories about the saloon have become part of Portland lore and attest to the significance of Erickson’s among the laboring class.

August Erickson immigrated from Finland in the early 1880s. Within a decade, he had established himself as a charitable publican, admired among loggers and laborers and known in those early years for his honesty in business and his commitment to hospitality. Erickson built the first of several eponymous saloons on the block of Second Street and West Burnside in the part of Portland known as the North End.

The 1894 flood was a defining event in establishing the reputation of Erickson’s Saloon. Erickson stocked a barge with liquor and “dancers” outside his submerged bar, and the story is that patrons floated in on everything from a sloop to a log, with some staying until their money ran out.

The saloon Erickson rebuilt after the flood was the setting for the so-called legendary years immortalized by Holbrook, a period roughly dating from the flood of 1894 to a 1913 fire. The structure, rebuilt on a half-block-sized piece of land, had three stories of excess. The cavernous main hall on the first floor was home to the “longest bar” and, according to writer Wayne Curtis, featured a “$5,000 pipe organ,” a free museum, a music stage, and imported oil paintings. The second floor catered to the wealthy elite and featured private card parlors, sedate bars, and a sumptuous Gentlemen’s Grill with tuxedo-clad waiters. The third floor was given over to roofless cubicles known as “cribs” that hosted sex workers and mistresses.

The main hall echoed with the music of a band, the stomping of dancers, and the laughter of the clientele, providing what was for some an irresistible draw. One patron, writing anonymously in 1925 for the Loyal Legion of Loggers and Lumbermen’s Four L Bulletin in a memoir titled “Erickson’s: A Logger’s Reverie,” recalled how “loggers and ranchers, railroad men and miners, fisherman and sailors, prospectors, cowboys, stakey men and stiffs; high and low, adventurers all, they came from everywhere” to revel in the “boisterous and hearty, but often rude spontaneity of rough men [who] had free rein.”

A free “Dainty Lunch” boasted a roast quarter steer, thick-cut bread, steamed clams, strong cheeses, mustards, and pickled fish—a substantial draw for working men. The selection of alcohol included sophisticated cocktails, an exclusive beer brewed by Henry Weinhard at an affordable nickel a pint, and cheap hard liquor that cost a quarter for two shots.

Erickson’s was an economic engine. The saloon employed at least thirty bartenders at the long bar alone, with additional bartenders at the other bars and a number of bouncers, bootblacks, sex workers, fruit sellers, waiters, dancers, musicians, card dealers, and chefs. The bartenders were notable for their meticulous mustaches and hair, as well as their wit, conversational skills, and general good nature. The bouncers were large and ferocious when confronted with those who insisted on breaking the saloon’s few iron-clad rules, among them a prohibition against begging and discussing politics or religion. Sex trafficking was a major part of the business. “At best,” Erickson’s 1925 obituary in the Oregonian noted, “the place August Erickson kept was a brothel, and at its worst it was an inspiration to rage and crime.”

The main clientele at Erickson’s was local, supplemented by tourists who brought in what former bouncer Spider Johnson estimated to be “50 to 500” customers at a time. It was also a center for itinerant laborers and a repository for messages delivered with the assumption that the recipient would eventually end up there. The writer in the Four L Bulletin remembered that the “songs of a dozen tongues” competed with one another in the main hall. The saloon was known as the House of All Nations for its willingness to serve foreigners, Blacks, and other minorities.

Erickson, an alcoholic, became the subject of frequent legal charges and arrests for offenses, including dispute over ownership of the saloon and illegal gambling. By 1906, he had sold a portion of his ownership to Fred Fritz Jr., who owned Fritz’s Saloon and Theater across the street, and J. J. Russell, who ran the Cabaret Grill next door, but he continued to work at the saloon as a manager and mascot, while also opening the Clackamas Tavern on Clackamas Road. After a 1913 fire damaged the saloon, he sold the remainder of his ownership to Fritz and Russell. He spent the rest of his life in penury and died in 1925.

The rebuilding of Erickson’s Saloon coincided with the advent of Oregon’s Prohibition laws in 1915. The bar sold soft drinks and “near beer” and charged for its once-free Dainty Lunch. By the time Prohibition was repealed, the saloon was a shadow of itself. The Fritz family owned the property until the 1960s, and the bar changed ownership multiple times over the years. An establishment with the name of “Erickson’s” operated on Second and Burnside before finally closing as Erickson’s Tavern in 1981.

Innovative Housing redeveloped the site as low-income apartments in the 2000s, using elements of the building’s history that included sections of the bar, a urinal trough, and a line of blue paint marking the height of the 1894 flood. A sign on the building identifies it as “Erickson’s Saloon 1895.”

End table/bedside table

20" x 20" x 26" T

8" Drawer

$ 1195.00

Erickson’s Saloon, sometimes called the Working Man’s Club or The Erickson Saloon, was a Portland establishment whose grandeur and notable size—epitomized by the 684-foot self-proclaimed “longest bar in the world” on its central drinking floor—ensured a national reputation that gave its glory years during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries an almost mythological reputation. The saloon’s lasting fame is largely attributable to writer Stewart Holbrook, whose 1954 Esquire article, “Elbow Bending for Giants,” remains the primary source for most writing on the subject. Stories about the saloon have become part of Portland lore and attest to the significance of Erickson’s among the laboring class.

August Erickson immigrated from Finland in the early 1880s. Within a decade, he had established himself as a charitable publican, admired among loggers and laborers and known in those early years for his honesty in business and his commitment to hospitality. Erickson built the first of several eponymous saloons on the block of Second Street and West Burnside in the part of Portland known as the North End.

The 1894 flood was a defining event in establishing the reputation of Erickson’s Saloon. Erickson stocked a barge with liquor and “dancers” outside his submerged bar, and the story is that patrons floated in on everything from a sloop to a log, with some staying until their money ran out.

The saloon Erickson rebuilt after the flood was the setting for the so-called legendary years immortalized by Holbrook, a period roughly dating from the flood of 1894 to a 1913 fire. The structure, rebuilt on a half-block-sized piece of land, had three stories of excess. The cavernous main hall on the first floor was home to the “longest bar” and, according to writer Wayne Curtis, featured a “$5,000 pipe organ,” a free museum, a music stage, and imported oil paintings. The second floor catered to the wealthy elite and featured private card parlors, sedate bars, and a sumptuous Gentlemen’s Grill with tuxedo-clad waiters. The third floor was given over to roofless cubicles known as “cribs” that hosted sex workers and mistresses.

The main hall echoed with the music of a band, the stomping of dancers, and the laughter of the clientele, providing what was for some an irresistible draw. One patron, writing anonymously in 1925 for the Loyal Legion of Loggers and Lumbermen’s Four L Bulletin in a memoir titled “Erickson’s: A Logger’s Reverie,” recalled how “loggers and ranchers, railroad men and miners, fisherman and sailors, prospectors, cowboys, stakey men and stiffs; high and low, adventurers all, they came from everywhere” to revel in the “boisterous and hearty, but often rude spontaneity of rough men [who] had free rein.”

A free “Dainty Lunch” boasted a roast quarter steer, thick-cut bread, steamed clams, strong cheeses, mustards, and pickled fish—a substantial draw for working men. The selection of alcohol included sophisticated cocktails, an exclusive beer brewed by Henry Weinhard at an affordable nickel a pint, and cheap hard liquor that cost a quarter for two shots.

Erickson’s was an economic engine. The saloon employed at least thirty bartenders at the long bar alone, with additional bartenders at the other bars and a number of bouncers, bootblacks, sex workers, fruit sellers, waiters, dancers, musicians, card dealers, and chefs. The bartenders were notable for their meticulous mustaches and hair, as well as their wit, conversational skills, and general good nature. The bouncers were large and ferocious when confronted with those who insisted on breaking the saloon’s few iron-clad rules, among them a prohibition against begging and discussing politics or religion. Sex trafficking was a major part of the business. “At best,” Erickson’s 1925 obituary in the Oregonian noted, “the place August Erickson kept was a brothel, and at its worst it was an inspiration to rage and crime.”

The main clientele at Erickson’s was local, supplemented by tourists who brought in what former bouncer Spider Johnson estimated to be “50 to 500” customers at a time. It was also a center for itinerant laborers and a repository for messages delivered with the assumption that the recipient would eventually end up there. The writer in the Four L Bulletin remembered that the “songs of a dozen tongues” competed with one another in the main hall. The saloon was known as the House of All Nations for its willingness to serve foreigners, Blacks, and other minorities.

Erickson, an alcoholic, became the subject of frequent legal charges and arrests for offenses, including dispute over ownership of the saloon and illegal gambling. By 1906, he had sold a portion of his ownership to Fred Fritz Jr., who owned Fritz’s Saloon and Theater across the street, and J. J. Russell, who ran the Cabaret Grill next door, but he continued to work at the saloon as a manager and mascot, while also opening the Clackamas Tavern on Clackamas Road. After a 1913 fire damaged the saloon, he sold the remainder of his ownership to Fritz and Russell. He spent the rest of his life in penury and died in 1925.

The rebuilding of Erickson’s Saloon coincided with the advent of Oregon’s Prohibition laws in 1915. The bar sold soft drinks and “near beer” and charged for its once-free Dainty Lunch. By the time Prohibition was repealed, the saloon was a shadow of itself. The Fritz family owned the property until the 1960s, and the bar changed ownership multiple times over the years. An establishment with the name of “Erickson’s” operated on Second and Burnside before finally closing as Erickson’s Tavern in 1981.

Innovative Housing redeveloped the site as low-income apartments in the 2000s, using elements of the building’s history that included sections of the bar, a urinal trough, and a line of blue paint marking the height of the 1894 flood. A sign on the building identifies it as “Erickson’s Saloon 1895.”

End table/bedside table

20" x 20" x 26" T

8" Drawer

$ 1195.00

Location263 Silverbrook Rd

Randle’, WA 98377 (509) 985-6844 |